Venter versus Collins (again) and the Race for Precision Medicine in the Petabyte Era.

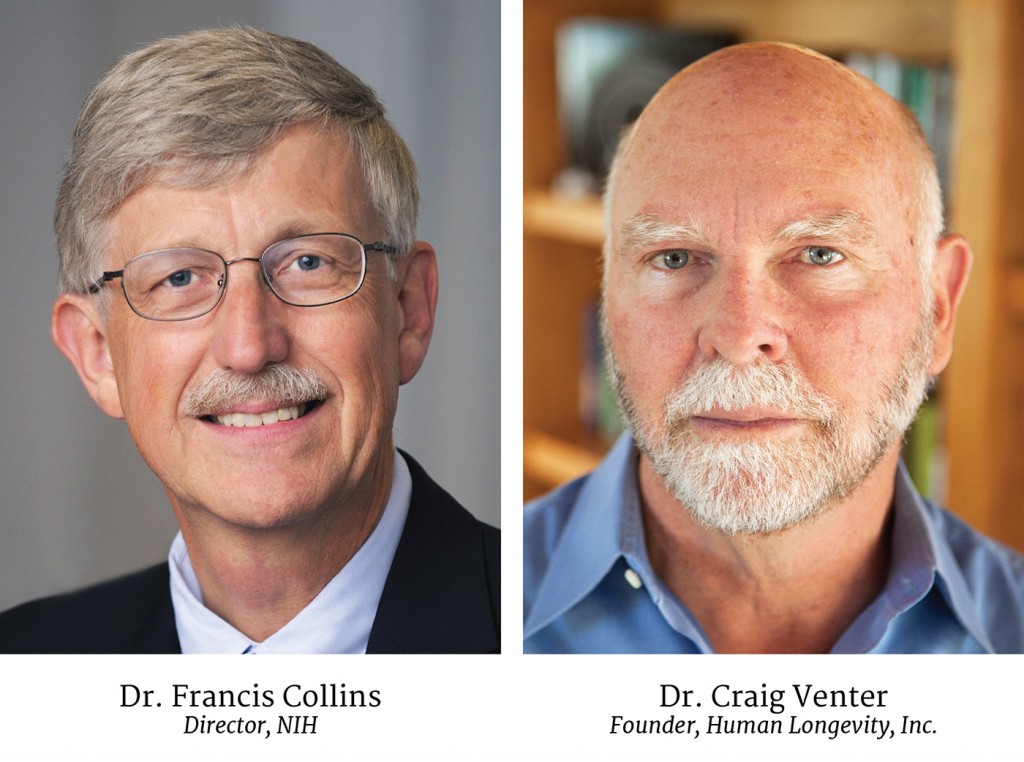

The Precision Medicine Initiative announced by President Obama in 2015 State of the Union Address has created quite a stir, with the overall tone being one of optimism for the future of personalized medicine. The driving force behind this enormous undertaking appears to be Dr. Francis Collins, Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), who also led the US Government’s effort in the Human Genome Project.

Collins outlined details of the government’s precision medicine initiative in a NEJM article, detailing the $215 million The White House has earmarked for the project as well as information on the “cohort of a million or more volunteers” mentioned in the same proposal.

Less known to the public, however, is what Dr. Craig Venter, the other pioneer of the first human genome sequencing effort, has been doing to further personalized medicine. Last year, he raised $70 million to found Human Longevity Inc. (HLI), and set a goal to sequence 1 million human genomes by 2020.

So…if we combine the presidential decree for a precision medicine initiative with two completely separate approaches (both contending to be this era’s “Master of Genomic Knowledge”), what do we get? Hopefully, the result is progress in the world of scientific and medical research.

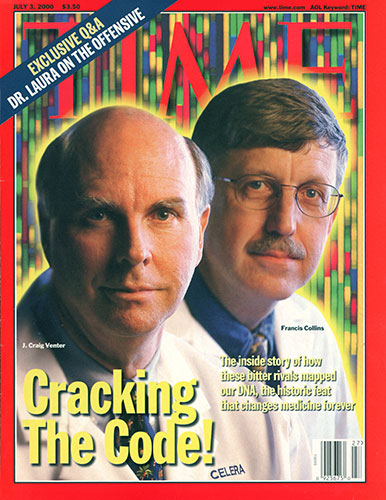

This isn’t the first genome war.

The original battle came to the public’s attention in May 1998, when the Institute for Genomic Research’s director Craig Venter announced his plans to map the human genome via his newly formed private company, Celera (the Latin word for ‘speed’). The NIH, led by Francis Collins (who was then at the National Health Genome Research Institute), was at the same time working on the Human Genome Project (the world’s largest ever science project) with an expected completion date that was 15 years away. The gauntlet had been dropped; the first party to finish mapping the human genome stood to transform the future of medicine. As might be expected, Venter’s announcement caused an acceleration of research activity by the government-funded genome teams.

In 2000, the war ended in a sort of graceful tie when both Collins and Venter met with President Clinton in The East Room of the White House and jointly announced the completion of the first draft sequence of the entire human genome.

Now, in 2015, it’s Venter versus Collins again. With Venter’s HLI already putting its $70 million to work, and Collins on course to deploy $215 million from the Fed’s pocket, the stage appears to be set in a big way for round two of the Genome War. Like last time, private funding will compete with federal dollars. However, this time, the goal is to sequence not one, but one million genomes.

Off to the Races

We call it a “war,” but that’s probably too extreme. Competition in genomics research can actually be a very good thing. Round one in the genome battle expedited genetics research by several years. Interestingly, Venter appears to have a significant lead once again; HLI has already sequenced “several thousand” genomes, with plans to scale to 100,000 genomes per year.

What is the ultimate prize of the competition? As with the first Genome War, the biggest beneficiary will likely be society as a whole: we’ll gain both genomic knowledge for the advancement of science and betterment of our collective health. Will these efforts unexpectedly converge and unify once again? We’ll have to wait and see. What is certain is that this matchup—$70 million of private investment in the hands of Venter’s HLI (epitome of both efficiency and free enterprise), vs. $215 million in a government initiative (which could potentially be much slower moving)—will be fascinating to watch.

—

If you’re interested, the first genome war was portrayed in James Shreeve’s book The Genome War. It’s a great read!